Blogs

It Was the Most Violent Prison in America. Then the Guards Went on Strike

Guards continued working at a fraction of the usual numbers and staying on outside detail, away from the prisoners. A funny thing was happening, something “probably unprecedented in the annals of the prison reform movement,” according to an op-ed in The Boston Globe. “Peace reigned. There was a calm and peaceful atmosphere. No incidents of violence or disruption were reported.” The NPRA’s leadership became a national story, a “story of hope that even fallible and finite creatures can claim a common vision and struggle together to attain it,” Rodman wrote in his introduction to When the Prisoners Ran Walpole.

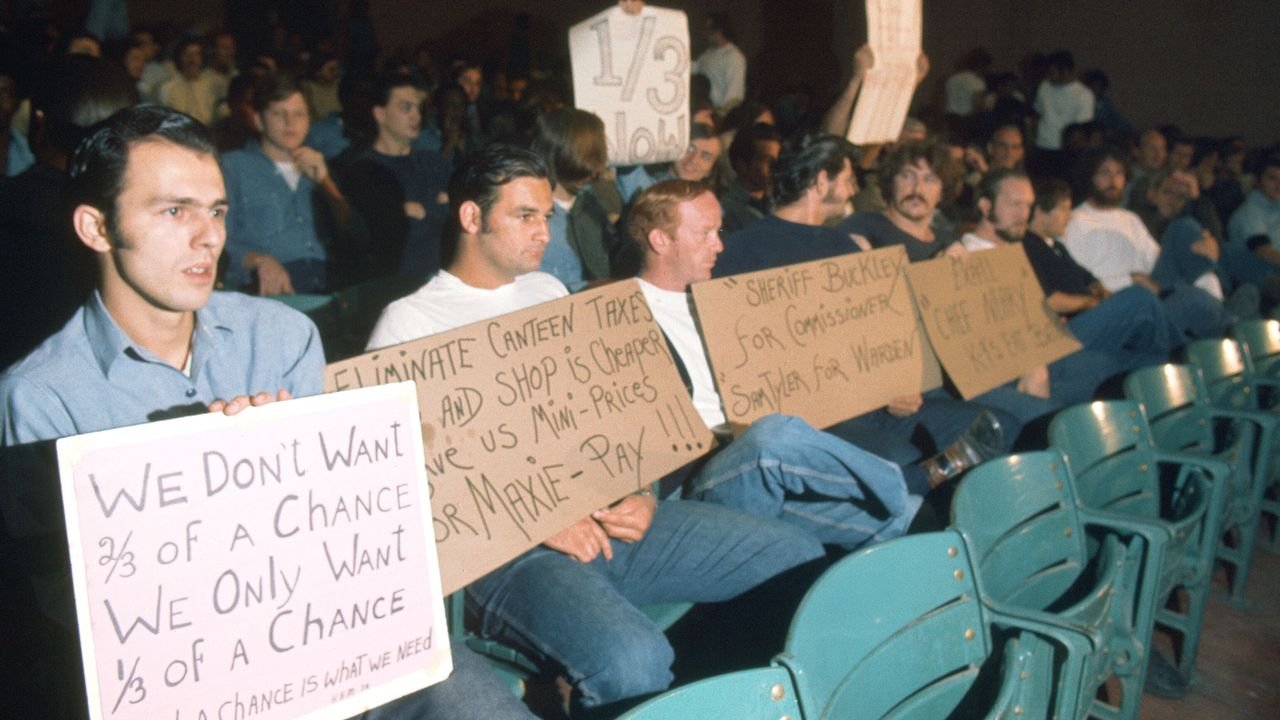

The men continued lobbying for the state to grant them collective bargaining rights for their union and to address their demands. One of those demands was a pay raise for the guards, an adjustment that the NPRA understood would benefit their quality of life as much as it would the officers. “We want to see Walpole changed so it’s compatible with the street—a community prison with self-government, inmate participation, and working conditions like on the street,” Dellelo said. “We’ve got to get guards and inmates together and see what we can live with.”

Both parties were skeptical of one another, Rodman said later, but the guards were curious. “They had never had those kinds of conversations, you might say, on an equal footing with the prisoners, and were surprised about some of the ideas the prisoners had about how the place could run better,” he told the BBC. “There came a point in those negotiations when half the prisoners and half the guards agreed on the same point and disagreed on the same point. I looked over and I saw the superintendent shake his head, and I said, ‘Well, that’s going to be the end of this,’ because there was too much potential for genuine cooperation. And that’s the last thing they wanted.”

Writing about a recent guards’ strike in New York state, the social anthropologist Orisanmi Burton observed that to this day, “guards remain unable to forge political solidarity by linking their abysmal working conditions with incarcerated people’s abysmal living conditions.” That’s no accident, he tells me. There’s a structure in place that creates economic incentives for guards to turn away from that solidarity, because if there’s no prison, there’s no job. The fact that both parties are “in different ways trapped in this grotesque institution tells us something not only about the institutions, but tells us about how the state values the life of its subjects, that the state understands both prisoners and guards to be disposable.”

Of course, at Walpole in 1973, the guards could choose to go home, and the prisoners couldn’t. One prisoner said that it was “nice and quiet, and nothing will happen until they let the guards back in.” The general population could exhale a bit.

As the months went by and the prisoners continued to lead the prison, Hamm suspected the calm would be short-lived. He wouldn’t abandon his position as a leader, especially not with the eyes of the country on Walpole, looking to see how things would shake out. “But for those of us in the front, if you weren’t afraid, there was something seriously wrong with you,” Hamm says. “And I was afraid.” He was terrified, he says, that the prisoners’ reign would end in state-sanctioned violence. “I watched what happened with Attica and I watched how they killed them kids at Kent State and I watched what they did at Wounded Knee,” he tells me. “I knew they could not let this go on for long.”

Boone left town for a few days in late May. One evening soon after, Dellelo was woken up by a group of distraught prisoners. Walter Waitkevich, the latest superintendent, had sent out a memo to the general population that a shakedown was set to begin soon. All visits would be canceled and the men would be confined to their cells for 48 hours. This would be enforced by the skeleton crew of guards and cadet trainees working the prison, and would be followed by bringing back the “pass system,” which was similar to hall passes in schools. The men had known about the upcoming shakedown, but the announcement that it would be done in such punishing terms was unexpected; no one from the NPRA was consulted, and the men were rattled by what they saw as the administration acting in bad faith.

Dellelo was able to call Waitkevich at home and convince him to meet in person. Several NPRA representatives and two civilian observers settled in the visiting room, ready to plead their case. Once everyone else was seated, Waitkevich entered the room, choosing to stand. We’re okay with the shakedown, the men suggested, according to minutes of the meeting taken at the time, but a 48-hour lockup and canceled visits during a shakedown? Unheard of. We’d like to be able to shower, we want to keep our visits, and we don’t want a return to the pass system. This is in the guards’ best interest, one of the men pointed out, because resentment about an unexpected and undeserved two-day lockup is likely to be taken out on them. Waitkevich waited until they were done, then responded to each point, explaining that this was the best way to reintroduce guards to the facility. After all, “screws have a right to work,” he said. And it was out of his hands, in any case—these decisions had been made by Boone’s top aides. The men were incredulous. “It’s your institution, you can do anything you want,” one said. “It’s not my institution, it’s your institution,” Waitkevich responded.